If curriculum is to reflect the goals of a school and the needs of its students, it makes sense for teachers to develop it them-selves. But how might they do it, and when? And is it better to adopt or adapt materials ‘off the shelf’ or should students and teachers be creating curriculum together?

If curriculum is to reflect the goals of a school and the needs of its students, it makes sense for teachers to develop it them-selves. But how might they do it, and when? And is it better to adopt or adapt materials ‘off the shelf’ or should students and teachers be creating curriculum together?

Five math and science teachers are sitting around a table piled high with books, papers, software packages, and empty coffee cups. They have a two-hour planning period; the halls ring with the noise of students who will show up in class next term with varying degrees of interest, skill, experience, and maturity. The school has promised a project-based curriculum that integrates mathematics, science, and technology around Essential Questions; and everyone is eager to see it work.

But despite months of wrestling with what they want kids to know and be able to do, this staff still feels overwhelmed by the task before it: to plan a thoughtful, deep, well-organized curriculum that draws forth those desired outcomes from every student. Shouldn’t they just pick one of these fine new textbooks and follow it? Why should they reinvent the wheel for this particular group of kids, in this particular community, with these particular teachers? What are they trying to prove-and when the state tests arrive in the spring, will their brave new ideas serve their students well?

This scene took place at a new Essential school, the Francis W. Parker Charter School in Fort Devens, Massachusetts, but it reflects the dilemmas felt by many Essential schools in other situations and circumstances. Though most faculties need not create an entire curriculum from scratch, many do aim to replace outdated coursework with new experiences that better match their goals for students. All schools now face increased pressure to meet the new standards flooding in from national and state professional groups and education boards. In state after state, new performance-based standardized assessments fit poorly with old curricula, and schools must decide whether to adopt new textbooks or create their own plans from a variety of sources.

Yet all other reasons to develop curriculum pale beside the bald reality that every school is different. When Essential schools commit to knowing their students well and to deepening their understanding by exploring less material in more depth, they must at once confront decisions about what and how to teach. Schools like this often recognize, moreover, that curriculum comprises not just content knowledge but every encounter among teachers, students, and community -everything that makes up understanding, and everything that demonstrates it. Seen in this light, the daily decisions that affect a school’s organization and culture, both in and out of the classroom, are already defining the curriculum as surely as the choice of what books to use.

Developing curriculum together also gives teachers the important chance to have ongoing, meaningful conversation with each other-about interesting ideas in their fields, about how children learn, and about ways to improve their classroom practice. The professional community this engenders, recent research by both Milbrey McLaugh-lin and Robert Felner has shown, has a direct link to higher student achievement. And this holds true whether such collegial conversation takes place in department meetings, in summer institutes, or by electronic mail with distant colleagues.

Still, developing curriculum takes more time and resources than most schools provide to teachers. Even in the best of circumstances it goes slowly, because the work takes place on many levels at once, from the most deeply personal to the most broadly systemic. (“It is easier to move a cemetery,” said Woodrow Wilson, “than to effect a change in curriculum.”) Examples of how to sustain the process are as different as the contexts from which they come, but in examining a number of Essential schools’ efforts, some broad outlines do emerge.

What Drives Curriculum?

Common sense and etymology tell us that a curriculum is a dynamic event, not an object-a river of experience that “courses” through student and teacher over the years of school, altering them both in myriad ways. Joe McDonald, a senior researcher at the Annenberg Institute, describes it as “one point of a triangular relationship, of which the other two points are the teacher and the students,” who each increase in understanding as they work through subject matter.

Seen this way, the first step to constructing a curriculum cannot be to decide what tidy package of facts a school will pass on to its student-clients. Rather, a school must decide the direction in which the course of events will flow-the place where, if the journey goes well, the students should emerge ready for another. Though the word “outcomes” has emerged from the past decade dirtied from the political fray, schools must still use it when they ask about curriculum, “Where and how do we want students to come out?”

But who has the authority to decide that? Even outwardly similar reform-minded schools display deep differences in how they answer, observes researcher Bethany Rogers in a study for the Atlas consortium to which the Coalition belongs. For some, the driving force may be national and state curriculum standards. James Comer’s School Development Project, chiefly concerned that students achieve equity in a system that privileges conventional curriculum, may emphasize standardized tests. A group like Foxfire gives student interest a larger role in shaping curriculum. And Theodore Sizer asserts that each local community must set its own expectations to reflect its particular needs and situation.

These philosophical differences about authority, says Rogers, underlie other conflicting, fundamental beliefs: “what good curriculum is, how it is developed, how it is related to whole-school reform, and how it accommodates kids and their diversity.” Getting clear on them from the start, then, will lend coherence and purpose to a school’s subsequent decisions and actions.

But the school that decides to plan its curriculum around standards has a big job to do at the start, whether it draws up those standards for itself or adopts them from national or state recommendations. Among other things, all kinds of “outcomes” and “standards” are strewn about the educational landscape these days. Some are linked to content, spelling out what students should know and be able to do within (and sometimes across) various disciplines. Some are linked to performance, defining what it looks like when students do something “well enough” for a particular level of accomplishment in a particular community. Some are linked to opportunity, describing the teaching and resources that children need to learn well. In 1995, when the federal Mid-continent Regional Educational Laboratory (McRel) in Colorado compiled into one database the leading published standards and their subcomponent “benchmarks” at various developmental levels, then edited out redundancies, they ended up with well over 1,500 benchmarks embedded within 157 standards.

Skills, Habits, and ‘Content’

Teachers who have attempted writing their own content standards, benchmarks, and performance tasks may well appreciate the help from such a database, if only in testing their ideas and words against those of others. But many Essential school teachers involved in curriculum development do not start with content at all. Instead they describe a vision of what they want students to “be” rather than to “do,” using terms such as “complex thinker,” “problem solver,” and “community contributor.” Such broad (and less measurable) outcome goals often show up in the form of a state’s “common core of learning.”

This often moves into a discussion of what skills students should acquire throughout their school years. “For several years our district has been focusing primarily on writing, reading, oral presentation, visual representation, and data analysis,” says John Newlin, a high school social studiesteacher in Gorham, Maine who serves as a district-wide “teacher leader” in curriculum, assessment, and instruction.

To get at those outcomes, Gorham has been urging teachers to develop “main course [as opposed to dessert] projects”-nutritious, academically rigorous projects that could lead students toward “understanding goals.” Task forces of teachers identified “essential questions” or themes they dubbed “enduring issues” (like “racial and cultural conflict or cooperation”). They called for “compulsory performances” that would demonstrate proficiency in the most important skills. In doing all this they came up with a useful template for designing a project-based curriculum. (See: Using a ‘Project Design Template’ to Develop Curriculum)

Still, for most subjects Gorham had not yet codified any required content their curriculum would cover. “We started all this before the national standards came out, but we realized we would have to pay attention to content-area knowledge,” Newlin says. So it helped, he says, when the state recently drafted the “learning results” it expects in various content areas, which will ultimately be reflected in Maine’s new performance assessments.

In states that do not issue such content standards, teachers may face the daunting task of doing it themselves. “We headed down that path in social studies several years ago, because we wanted a more coherent program across grade levels,” Newlin says. Though the results mesh well with the state’s requirements, he says,”It entailed a huge expenditure of our time and energy over several years. It’s so hard to get agreement on what to include, and on how specific to make content standards.” Schools in this situation, Newlin suggests, might instead send away for good models from elsewhere, and then take a few months to study and adapt them.

For example, Parker School teachers scrutinized a set of “per-formance standards” and assessments just released by New Stand-ards, a collaboration of the Learning Research and Development Center at the University of Pittsburgh and the National Center on Education and the Economy. “You don’t want to set up a situation where people don’t have to think. But you can save them a good deal of labor,” says Ann Borthwick, New Standards’ director of standards, development and applied learning. By providing standards on one end and assessments on the other, she says, “we hope to help schools as they fill in the middle for themselves with a large, rich curriculum that leads students toward common standards. We hope schools will use our work to ask, ‘What would have to be different to make these standards work for us?'”

Building a Framework

Gorham’s task force of social studies teachers spent much of its time thinking about how to frame its work so that the curriculum would hang together across grade levels without prescribing coursework too closely. “We had to create a filter system to identify what information students really needed in order to participate in the public issues of the day,” Newlin says. “If we couldn’t reduce the total quantity of terms and concepts we wanted students to understand, we wouldn’t have time for the projects through which they could practice the skills and activities we wanted them to be able to do.”

In the end the group wrote over 80 pages of text, a menu from which teachers could draw to design projects at various grade levels. “Each grade level had its historical time period or geographic focus,” Newlin says. “We used ‘enduring issues’ as through-lines students revisited again and again.”

The Gorham district drew help and resources from its relationship with the Atlas Communities Project, a consortium funded by the New American Schools Develop-ment Corporation (Nasdc) and jointly developed by the Coalition of Essential Schools, Harvard Univer-sity’s Project Zero, Yale’s School Development Program, and Educa-tion Development Center. In fact, the Atlas Curriculum Planning Framework (some of which is condensed on page 4) echoes the structure that Gorham used in identifying its curricular purpose and strategies.

“The framework is a way to pull out the most interesting topics, issues and questions of existing curricula and reframe them in a way that promotes critical inquiry, discourse, and intellectual work,” says its author, Michael DeAngelo. “But it maintains academic integrity by focusing on the concepts, principles, and lessons important for students to understand.” To do this, the framework uses four “content” components (generative topics; issues, problems, and challenges; essential questions; and “essential understandings”) and four that focus on building and assessing understanding (essential skills and habits, performances and exhibitions, ongoing assessment strategies, and performance standards and scoring rubrics).

The best curriculum frameworks are designed so that students revisit and connect content areas, deepening their understanding over the years from kindergarten through high school. In McFarland, Wiscon-sin, Deb Larson was one of 25 educators chosen by Project 2061 to develop a K-12 curriculum based on the concepts expressed in Science for All Americans, the manifesto of the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences (AAAS). “We soon realized it couldn’t just be a science curriculum,” Larson says. “We’d be fixing one part of the system at the expense of the rest of the system.”

Instead, the McFarland team spent four years crafting 52 cross-disciplinary “vistas”-a series of “engaging experiences,” Larson explains, “crafted so they connect with one another, and organized into twelve areas of continuing human concern-food, water, energy, communication, shelter and architecture, and so forth.” Students would revisit each of these areas in depth at least four times from kindergarten through high school, as they worked through progressively more complex projects.

Too bold for the McFarland schools, the framework belongs now to Project 2061, and Larson does not know if anyone has ever used it; but a more fully integrated and extensive approach would be hard to find.

Students at the Center

Working out the framework of a curriculum can be so absorbing, some teachers caution, that it overshadows the living students at its center. Though few schools would risk going into a year without lesson plans in hand, many educators argue that involving students in developing curriculum is crucial. “The question of what should be at the center of the curriculum should be at the center of the curriculum,” declared Deborah Meier, Jay Feather-stone, and Bill Ayers at a 1991 meeting of their North Dakota Study Group.

“Every decision we make about what kids will do takes a learning experience away from the child,” agrees David Ruff, who works with the Coalition, Foxfire, and other reform efforts at the Southern Maine Partnership. “The danger is that teachers start to think of curriculum as activities for kids to do, rather than knowledge they should gain or skills to develop. As long as you have a clear picture of your outcomes, I believe that kids themselves should be creating the activities that will get them there.”

That doesn’t mean abdicating the teacher’s guiding role in curriculum, he observes. Starting students out with more structure helps them work up gradually to more independent choices. “I tell kids that some things are givens-the skills and content they need to end up with,” Ruff says. “As long as they can demonstrate they have them, I don’t care how we learn them.”

When he taught fiction to high school English students in Saco, Maine, for example, Ruff’s students wanted to hang out at the local mall for a day in order to study the elements of fiction in their lives. “I asked them to show me clearly how that would deepen their understanding,” he says, “and they ended up choosing another activity.”

Many Essential school teachers use the student-centered Foxfire approach as a way to work toward agreed-on goals while drawing on students’ authentic concerns and interests. “For me Foxfire holds the most important keys to success in planning curriculum for the heterogeneous classroom-the student voice and choice,” says Edorah Fraser, who teaches at Souhegan High School in Amherst, New Hampshire. “Giving students choices is the only thing that I’ve found that works-choices among readings around a common theme, among research topics, and so forth.”

Carol Lacerenza-Bjork and her ninth-grade English students at West Hill High School in Stamford, Connecticut decide together on a theme for their course and choose a few central texts. Then students branch out through a variety of seminars and other performance tasks based on their own choices. (See Horace, Vol. 11, No. 2, November 1994.) And at Rochester, New York’s School Without Walls, teachers and students routinely design curricular projects together, using guidelines principal Dan Drmacich has devised. (See below)

Grounding the curriculum in questions and activities that students choose raises their commitment and achievement level, say teachers who have tried it. As part of their foreign language classes, for example, many California students choose “cultural participation and research” activities in the community, from learning to dance the merengue to shopping at a Spanish market or exchanging dollars for pesetas. The approach, developed by Suzanne Charlton and Cynthia Leathers at the University of California at Irvine, asks students to document and reflect on their projects in portfolios, and it awards points for activities based on their degree of challenge.

“It’s easy for a language curriculum to neglect the very rich culture of students themselves,” says Charl-ton. “When kids go out and use another language to explore things they are really interested in, whether it’s cooking or watching a movie, they start to develop proficiency in ways that reflect their own particular intelligences.” Such experiences lead naturally into other subject areas, she notes, and teachers who use this approach often find their curriculum becoming “interdisciplinary” despite themselves.

Teams Building Curriculum

Typically, teachers develop curriculum one unit at a time, often in teams that attend workshops or summer institutes. When Steve Cantrell taught at Rancho San Joaquin Middle School in Irvine, California, most teachers worked on curriculum units for a week in the summer. “We shared a lot of the same resources, but each of us was paid to create one new performance assessment,” says Cantrell, who now coaches a Critical Friends Group at Whittier High School, near Los Angeles. “With several such weeks a year, a faculty could transform its curriculum over four or five years.”

If teachers see developing and trying out curriculum together as part of strengthening their own teaching practice, they are less likely to leave it to outsiders, Cantrell believes. “Imagine a team of teachers sharing their results, then giving each other steady feedback during the year as they tested out ideas in their classrooms,” he says. “When you’ve helped to shape other people’s work, you understand their train of thought better and are more able to draw on it. That’s why people who develop curriculum in central offices often don’t see it used by teachers.”

But developing curriculum in a team involves a complex mix of attitudes and assumptions that can make or break the effort. Kellogg’s educational foundation gave Michigan’s Caledonia High School $450,000 to develop a ninth- and tenth-grade curriculum integrating science, technology, agriculture, and natural resources. The experience challenged the seven teachers who spent over three years on the project, using an extra daily planning period, release days, and paid weeks in the summer.

“We did quite a lot of teambuilding activities from the start, but even though we could agree on a general vision we had different opinions and viewpoints,” says ninth-grade science teacher Mike Fine. “We tried to keep ourselves focused on scientific processes and the thinking skills of good scientists. Then we used a systems approach to content: we identified fifteen systems that integrated one or more areas of science, and put them together in the form of projects.”

Developing the habits of inquiry proved critical to the teachers’ efforts. “We began by reading everything we could get our hands on,” Fine says. Kellogg’s funding paid for the team to visit other schools and institutions as far away as California and even Scandinavia. “Anything that could help us get out of the bubble, we did,” he recollects. “We went to innovative museums, aquariums, and companies; we talked to as many experts and outsiders as we could.” Even visiting other classrooms within one’s own district, Fine observes, is a challenge for most teachers.

New technologies also contributed substantially to widening the Caledonia team’s horizons. “Anyone who does this should get their hands on as much technology as they can and get students and teachers both using it,” Fine says. “There’s so much great stuff out there, and now you can use the Internet to talk to other teachers and experts all over the place.”

Before, during, and after the curriculum development process, the Caledonia team faced pressures from every quarter to keep the curriculum within conventional bounds. “No one grew up learning science this way,” Fine observes. “We’ve been forced to modify the approach to make people more comfortable.” He laughs. “I have to admit it would be more comfortable to teach the old way, too. I could just get out the textbook and coast.”

Keeping up the team nature of the innovations also proved difficult once the curriculum was in place. Caledonia is organized into ninth, tenth, and junior-senior teams, so the ninth- and tenth-grade teachers who wrote it together now find little time to work across grades. “It’s frustrating when I can’t answer all the parents’ questions on what the tenth grade is doing,” Fine observes.

These practical adjustments in what Joe McDonald refers to as a school’s “wiring”-its distribution of energy, information, and power-can determine how well teacher-developed curriculum works. “It’s not just a matter of substituting one set of activities for another,” notes John Watkins, the ethnographer who evaluated Caledonia’s project. “It’s the most fundamental change on a personal and professional level. That’s why it’s so hard. Many teams end up recreating their districts in microcosm.”

Perhaps that explains why so many of the Essential school teachers who are successfully developing curriculum have the full encouragement of their district, their state, and often of outside partners as well. They may belong to networks of like-minded teachers, such as Foxfire. They may call on the resources of a nearby university, as with Gorham and the University of Southern Maine. They often have easy access to the Internet and its rich bank of collegial advice and support from near and far. Many teach in teams, which share regular planning time during the school day. They get training in working as a group. They feel welcome in each other’s classrooms; they get out and visit other schools. They expect to work with colleagues in summer institutes or weekend workshops, and they are paid to do so. They read.

“Our district has shown tremendous support for thoughtful risk taking over the past ten years,” says Gorham’s John Newlin. “If you’ve done your research and talked with other people who have tried something, they’ll say, ‘Go ahead’; they understand that you might not succeed and back you up if you don’t.”

A push from the district or state, in fact, can sometimes catalyze the need to develop new curriculum. Gorham’s new requirement for every teacher to use portfolio assessment has moved most teachers to develop classroom projects to put in them. In California, 144 schools that have taken the lead in curriculum and assessment receive extra funding under the state’s Restructuring Initiative. National associations like the AAAS often light a fire under outdated approaches by supporting large-scale curricular projects like Project 2061. Even a push to turn around high dropout rates or to meet the needs of an underserved population can spark the grass-roots development of new ideas for what and how to teach.

Adapting What’s Out There

Since creating a curriculum from the ground up takes more resources and experience than most teachers have, what about using packaged curriculum? Textbook publishers, after all, have responded to the shift in the educational climate by developing lavish textbook series complete with technology add-ons that would leave most home-grown efforts by teachers in the dust. Years in the making, these curricula are usually carefully aligned with various national standards and thoroughly vetted for the kinds of oversights a teacher’s own work might contain.

Yet often such ready-made curricula leave little room for the unique and particular learning situation, several experienced Essential school teachers agreed in a recent Coalition seminar on curriculum development. Rather than focusing on “teacher-proof” curriculum, they suggested, professional development opportunities should model how teachers can turn the given into something owned by both teacher and students.

Such ownership does not depend on having created the piece of curriculum, but has to do with “adjusting curriculum to our timing, our group of students, our school culture, our community culture, our classroom, our own personal strengths,” these teachers reported. Good teachers, they said, know “what to emphasize, what to stretch out, what to deepen.”

“To teach well, teachers must have a relationship with what they teach, as well as with the people they teach it to,” Joe McDonald agrees. “They must interact with both, not just deliver one to the other.” Instead, he urges, “Imagine curriculum as the set of learning opportunities available to both teachers and students as a result of their connectedness to each other and to outside experience and expertise.”

Even curriculum she has developed herself becomes stale, notes Eileen Barton of Chicago’s Sullivan High School, if she does not continually work at opening it to redirection, evolution, and change. “Rather than getting richer over time, it can grow unwieldly and diffuse,” she says. “Even techniques like Socratic seminars, cooperative learning, and class projects can be dead if one doesn’t think them through again. Unless I reinvest myself in them, even my ‘best’ curriculums are sometimes better suited for show-and-tell with colleagues than for use with kids.”

Teachers often create innovative curriculum by borrowing from each other, from innovative textbooks and computer software, from education research organizations, and from public service agencies that produce educational materials. Scanning the catalogs of book and software publishers can yield rich supplements to a curriculum plan, and in an hour of Web browsing on the Internet, a teacher or information specialist with her ear to the ground can connect with hundreds of organizations eager to share resources. The Coalition and many other reform networks sponsor active on-line discussion groups in which school people regularly trade their experiences and suggestions. And in curriculum institutes at the growing number of regional centers for Essential schools, teachers can develop and share their questions, approaches, materials, and insights.

But with the wealth of ready-to-wear curriculum materials on the educational racks, does it make sense to go to the trouble and expense of a custom design? You’ll know by the fit, experienced teachers answer. An off-the-shelf package can look fine in the box; but does it move when you move, or does it pinch? Does it trip you up at just the wrong moment? Take the time to find out, they advise. With a tuck here and a tweak there, with a few idiosyncratic accessories and adjustments, you might just make someone else’s curriculum fit. If that doesn’t work, why not get together with a few friends and sew your own?

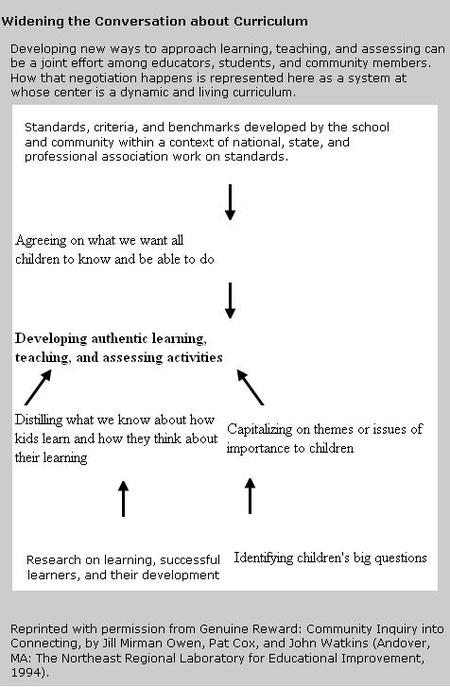

Widening the Conversation about Curriculum

Developing new ways to approach learning, teaching, and assessing can be a joint effort among educators, students, and community members. How that negotiation happens is represented here as a system at whose center is a dynamic and living curriculum.

PLEASE SEE THE GRAPHIC AT THE TOP UPPER RIGHT PAGE.

Reprinted with permission from Genuine Reward: Community Inquiry into Connecting, by Jill Mirman Owen, Pat Cox, and John Watkins (Andover, MA: The Northeast Regional Laboratory for Educational Improvement, 1994).